Exodus 12:1-4, 11-14

Psalm 116

1 Corinthians 11:23-26

Mark 14:1-25

Mark 14:1-25

This story of the extravagant woman is sandwiched between

two nasty bits of anger, vengeance and betrayal. This seemingly insignificant story,

often forgotten in the rush of Holy Week, as we make our mad dash from Palm

Sunday to Easter, is actually a story the church has preserved carefully over

the years. Indeed, along with the scrupulously remembered accounts of the Last

Supper and Passion of Jesus it likely formed an important part of the liturgies

– the worship services – of early Christians.

The story opens in a house. In the Gospel of Mark, lots of

important things happen in people’s houses: “in the house,” or ἐν τῇ οἰκίᾳ

in Greek, was where Jesus healed the sick, forgave sins, ate with sinners –

many times. Jesus went “in the house” to teach his disciples, to talk about the

coming kingdom, and from which the disciples were sent into the community. In

the decades between Jesus’ life and the writing of this Gospel, “in the house”

was where Christians gathered for worship. Churches were house churches, small,

domestic, private places. When Jesus ate the Passover meal with his friends,

the house was also the place from which he was betrayed.

It was probably not uncommon for a men’s-only dinner like

this one – not the Passover meal, but the meal where the woman anoints Jesus –

for women to come in to “entertain” the guests. But this is far from an

ordinary meal. First of all, the house belongs to someone profoundly unclean,

and unholy: Simon the leper – a shocking contrast to what we read before and

after the story, about the very holy and very clean chief priests and scribes.

So our location is already someplace very dicey, very on the edges of proper

society. Jesus and the disciples are eating with a leper, in the home of a

leper, on evening before the first night of Passover.

And if we take those brackets in further – “the clean”

contrasting with “the unclean” – we see at the center of the story the outraged

disciples. Who does this woman think she is, wasting all this valuable stuff.

They are pious, they are angry, they scold. But on either side of their pique,

we see the signs of the kingdom.

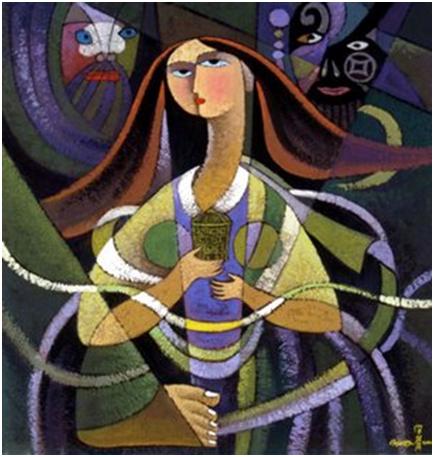

The woman’s alabaster jar of nard was indeed very valuable.

Nard was apparently passed on from mother to daughter, a family heirloom. The

oil is aromatic, beautiful, and used for healing. It is full of blessings. And

so this woman takes all she has – the most valuable thing she has – her most

precious asset – and pours it out on Jesus’ head. It is the kind of gesture we

hear echoed in marriage vows: “with all that I am and all that I have I honor

you.” When the early Christians heard this, in their house churches, years

after the reality and memory of the resurrection brought them together, they

would think of Jesus: God’s most precious gift, poured out completely, emptied

entirely on their heads, extravagant, wasteful, overflowing and abundant. This

woman’s act, to the ears of the early Christians, was a sign of what God had

done for them, and a mark of true discipleship.

Then, in the story, we have the outraged disciples, and then

framing them on the other side, we have Jesus’ words about what this woman’s

act means. It is an act of sacred charity, of care for the poorest and emptiest

person in the room. As the early church understood it years later, it was the

woman and the woman alone who knew what Jesus was about to do, and it was the

woman who took care of Jesus, who prepared him for the death that was to come.

This woman embodied the Good News, the Gospel. The woman, with her love and

charity and hope and confidence, is the prime example for the Christian life.

This 14th chapter of Mark goes back and forth between

betrayal and love, greed and abundance. But it is the unnamed woman who enters

the house of the leper, who leads us into the darkness of the crucifixion, who

is our model for what it means to follow Jesus. It is the women, marginalized

and insignificant, who stand, unnoticed, at the foot of the cross when the

disciples run away. And it is the women, who sneak into the burial garden at

dawn, and who are the first ones who run to tell us what they find there.