Proper 7-A; June

22, 2014

Genesis

21:8-21

Psalm 86:1-10, 16-17

Matthew

10:24-39

Because of his wife’s jealousy of the “other woman,” Abraham

casts his first-born son into the wilderness to die. Hagar, the Egyptian slave

woman who is the child's mother, has run out of food and water. She lays the

exhausted, parched and famished boy under a bush, and says, to no one, for

there is no witness to this act, "Do not let me look on the death of the

child." She then cries aloud and weeps.

This could be a scene from South Sudan, from the Mexican

border, from Syria, or from countless desperate places on our planet today,

where mothers and children are abandoned by family, by warring governments, by

economic forces beyond their control, and sent out to many kinds of wilderness

to die. Friday was World Refugee Day, and a good thing, too, because I hear

that today there are more refugees than at any time since the end of the Second

World War.

If the day's Gospel lesson reflects Jesus’ “family values,”

it does not fare much better. "I have come to set a man against his

father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her

mother-in-law." Jesus declares. "One's foes will be members of one's

own household. Whoever loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of

me."

This passage comes from a section in the Gospel of Matthew

concerning discipleship: what does it mean to follow Jesus? What would it look

like in my life, the disciples are asking themselves, to take part in the

breaking in of this kingdom of heaven? What does it mean to take up my cross,

to lose my life, to understand God not as the bringer of peace but as the

wielder of a sword?

As important as family is to us today, our modern ears

cannot hear it quite the same way as Jesus’ followers would have. We moderns

are all about “ME,” about self-actualization and self-realization. We strike

out on our own, we value independence and self-reliance: the Lone Ranger, the

pioneer on the frontier, the corporate raider, the “Army of One.” But in the

world in which Jesus lived, you were not an individual apart from your family.

Your family gave you your identity, gave you not just your name but your place

in the community and in the world, and your family protected you from that world.

Your family was a good thing, a precious thing; you didn’t just strike out on

your own. Jesus isn’t some 1960s hippie cult leader telling you to tune in,

turn on, drop out, from a family that oppresses, abuses or bores you.

There were plenty of bad things in first century Palestine,

plenty of things that Jesus might exhort you to leave behind, but the family

was not one of them. The Romans were bad, because they were an occupying army

in your homeland. The temple authorities were bad, because they colluded with

the Romans in exchange for privilege and protection. The civil bureaucracy was

bad, because it taxed the people nearly to death. Indeed, death and fear were

the operative social norms. The family was the refuge from all that. No one

could survive without a family.

So when Jesus says, “Follow me,” he is asking the disciples

to leave behind one of the few institutions in society that works. Jesus’ call

upsets every apple cart there is, and then he says, don’t worry. Don’t be

anxious. Consider the lilies, remember the sparrows. The kingdom of heaven

means the whole world is about to be re-ordered. Everything will be uncovered.

There will be no more secrets, no more power brokers, or back-room deals. This

news is so good that it must be shouted from the rooftops – no matter what the

consequences. No matter how many authorities you anger, no matter how many

armies they unleash. God’s kingdom HAS to challenge this kingdom, and even the

blessed and good family, the loving parents, the bonds of affection and kinship

– even these can get in the way of this truth of God which cuts like a sword.

The new thing which God is doing is even deeper, even more important, even more

powerful that the deepest, most important and most powerful parts of our lives,

the parts of our lives that make us most truly human. God is a sword which

pares away even our relationships, our kinships, our families.

Where is God taking us with this confusing, and maybe even

terrifying, lesson? Is discipleship some sort of desert wilderness? Are we

called to be like Hagar and Ishmael, stumbling around until the water runs out,

cut off from family and security and hope and the future?

Look again at this astounding story of Hagar and Ishmael –

and God. Even though God has apparently blessed the dismissal of the two into

the wilderness, God will not let them suffer. The voice of the angel of God

raises Hagar’s hopes, and promises that even this discarded son of Abraham will

be the father of many nations. Even these two hopeless creatures, these outcasts

and discards, this tiny remnant of a broken family will have a great future in

store. Abraham may have cast out Ishmael but God stayed with him.

If Jesus calls us as disciples to turn away from even the

good parts of our lives, if they distract and keep us from the gospel, it is

because being a disciple leads us into so much more. We see this broken world

now as Jesus sees it. Freed from our own particularity, we can act as perhaps

Jesus would have us act. We can even take our families with us. We can see the

Hagars and Ishmaels of today, in the countless desert places, the violent

streets, the lonely corners. We can resolve to be that angel of God who shouts

from the rooftops that it doesn’t have to be this way, the angel who brings

God’s gifts of water, sustenance and hope to a world that too often cries in

despair.

Proper 29 C Nov.

24, 2013

Jeremiah 23:1-6

Canticle 16 – Luke

1:68-79

Colossians 1:11-20

Luke

23:33-43

One of the founding stories of our democracy is “no taxation

without representation.” It is hard indeed, after all these years, built on

stories like that, to get our American heads around the Sunday of “Christ the

King.” Many Christians now call this day “the Reign of Christ,” which seems to

downplay the patriarchal tint to the word “king,” but the monarchy is still

there: we small-d democrats and small-r republicans have no intention of living

under anybody’s “reign” – monarchs reign; in a democracy, our leaders govern

with the consent of the people. We are citizens, not subjects, and even at

times like this, when our democracy seems a little bit lumpy and not working as

well as we would like, we’re not going back to be under anybody’s “reign.”

Yet our most frequently used prayer goes like this: “Thy

kingdom come. Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day

our daily bread, and lead us not into temptation.” No matter what our system of

government is, apparently the best way we can describe what the world should be

like is that it is under the reign of God – a reign under which all basic human

needs, like that of daily bread, are met, where “structures of domination and

subjugation [are] overcome… [where] all dwell in harmony with God and each

other

[i]”

beyond the temptation and corruption of evil.

If we Americans live in a democracy, yet with this memory of

monarchy, the people of Jesus’ day found themselves living in an unjust

monarchy, yet with a memory of democracy – or at least of republican

government. They remembered the rule of law. They remembered when their

wretched taxes did not go to support an imperial military force that imposed

order whether it was lawful or not. The days of Caesar Augustus, as the

evangelist Luke is so keenly aware, are the days of the first emperor, the

emperor who wrenched power from the elected consuls, now no more than the shell

of republicanism. “All the world is at peace,” Caesar declared. “First victory,

then peace.” The people longed for order and for peace. They longed for a

society in which they could safely earn their daily bread, a society which kept

at bay for the forces of chaos and disruption. But under the emperor, who

needed all those rumors of war to stay in business, peace came from a permanent

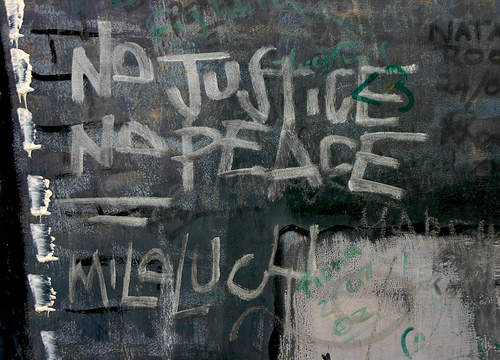

military. Peace came at the price of crippling and permanent taxation from

which there was no hope of relief. Peace came at the price of the erosion of

the rule of law. Peace came at the price of justice.

The Jesus mocked as “the king of the Jews” has no power to

impose anything like the peace and order of the Roman Empire. By the time this

Gospel is written, decades after anyone alive had witnessed that crucifixion,

people were beginning to understand what this “reign of God” meant – what this

alternative kingship was about. Jesus went to his death talking about a

different kind of world order. In his life and in his death, Jesus ‘[grappled]

with the disorders of injustice, suffering and death. The darkness of death,”

writes Biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann, is pushed back one emergency at a

time.” Over the course of his life and in the manner of his death, Jesus

demonstrated to ordinary people – like us – that he knew just what they were

going through, that he stood with them, and us, and that most importantly he

WITHstood the worst that lawlessness and chaos could dish out.

People knew that Luke wrote the truth about Jesus. They knew

it because the people who stood up for

them, and with them – the people who

were willing to go to their deaths in place of them, were the people who

believed in this upside-down kingship of Jesus. The people of Luke’s day knew

they could pray to the Emperor all they wanted, but there was no bread without

justice, no peace without justice. The imperial army could be powerful and

rich, but the people still suffered from want and lived in fear. The people of

Luke’s day began to follow “the servants of this new king. [These]

practitioners of this newly ordered world” took their leadership public. When

Luke told this story of standing at the foot of the cross, of hearing in Jesus’

last words that he was still turning the world around, it gave people courage that

they could do that too, in their own day and in the face of their own

challenges.

This day of Christ the King is for us, citizens and subjects

alike.